How Natural Gas Supply Chains Work for Power Plants

Share

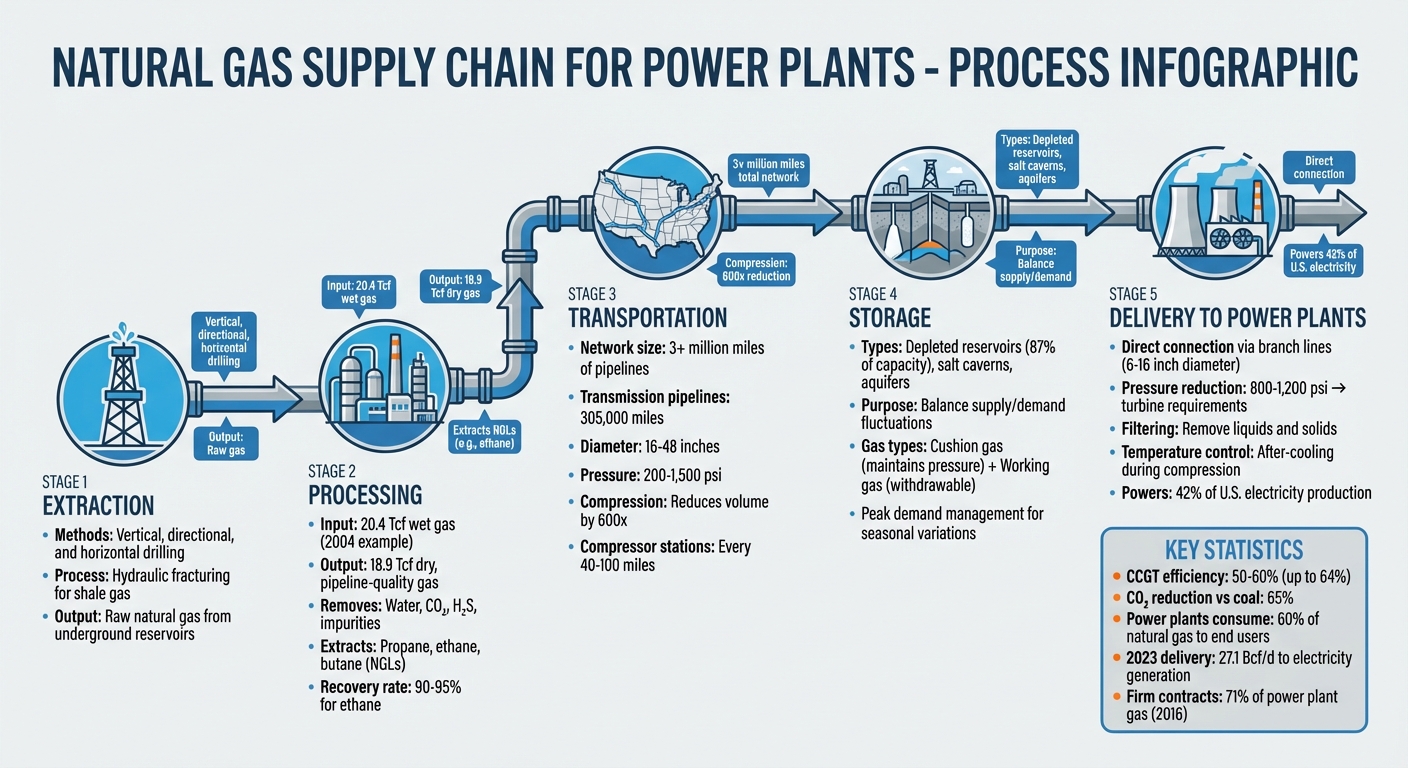

Natural gas powers 42% of U.S. electricity production (2024) and is a primary energy source for power plants due to its flexibility and reliability. Its supply chain involves several key steps:

- Extraction: Gas is drilled from underground reservoirs using methods like vertical, directional, or horizontal drilling. Hydraulic fracturing is often used for shale gas.

- Processing: Raw gas is refined to remove impurities (e.g., water, CO₂, H₂S) and extract valuable byproducts like propane and ethane.

- Transportation: A vast pipeline network (over 3 million miles) moves gas from production sites to power plants via high-pressure transmission pipelines.

- Storage: Gas is stored in underground reservoirs or salt caverns to manage supply and demand fluctuations, especially during peak periods.

- Delivery: Conditioned gas is delivered directly to power plants, bypassing local distribution networks, ensuring a steady fuel supply.

This system ensures natural gas is delivered safely and efficiently to power plants, supporting grid stability and electricity generation. Natural gas-fired plants are highly efficient, with combined cycle systems achieving efficiency rates of 50%–60% while reducing CO₂ emissions by 65% compared to coal plants.

Natural Gas Supply Chain: From Extraction to Power Plant Delivery

Extraction of Natural Gas

Before drilling begins, experts rely on tools like seismic surveys, aerial photography, and 3D projections to pinpoint underground gas deposits. These methods help map out the size, shape, and structure of reservoirs, ensuring a clear understanding of the site before any physical work starts. Once a location meets the necessary criteria, an exploration well is drilled to confirm whether the deposit is commercially viable.

Drilling and Well Development

Drilling techniques are chosen based on the reservoir's depth and location. Vertical drilling heads straight down to access deposits directly beneath the rig. Directional drilling, on the other hand, is angled to reach targets located to the side of the drilling site. Then there’s horizontal drilling, which begins vertically but curves to run horizontally through the gas-rich formation, maximizing the extraction area.

To ensure stability and environmental safety, steel casing is installed during drilling and is cemented in place. This casing protects groundwater and prevents the well from collapsing. At the target zone, the casing is perforated to allow gas to flow in, and production tubing is added to transport the gas to the surface. For shale formations, hydraulic fracturing - a process that injects high-pressure water, sand, and chemicals - creates fractures in the rock, releasing trapped gas.

"The ultimate goal of the well design is to ensure the environmentally sound, safe production of hydrocarbons by containing them inside the well, protecting groundwater resources, [and] isolating the productive formations from other formations." – Energy Infrastructure

Separation at the Wellhead

Natural gas doesn’t come out of the ground in a pure state. As it reaches the surface, the pressure drop naturally separates it from crude oil and water. At the wellhead, gravity separators are used to divide these components: heavier liquids like oil and water settle at the bottom, while the lighter natural gas rises to the top.

To further refine the gas, scrubbers remove sand and other solid particles, while small gas-fired heaters prevent methane hydrates - ice-like blockages - from forming in colder temperatures. For wells with high pressure, Low-Temperature Separator (LTX) units rapidly cool and expand the gas to condense out oil and water. This early-stage separation eliminates free water and lease condensate (heavy hydrocarbons like pentane) before the gas is sent through gathering pipelines to processing facilities. Once separated, the raw gas moves on for further purification at processing plants.

Processing Natural Gas to Pipeline Quality

After the initial separation, natural gas still contains impurities that make it unsuitable for pipeline transport. Processing plants refine this "wet" gas into "dry", pipeline-ready fuel by removing contaminants and extracting byproducts. For example, in 2004, the U.S. processed 20.4 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of wet natural gas, converting it into 18.9 Tcf of dry, pipeline-quality gas. This transformation is a crucial step in preparing natural gas for safe and efficient transportation.

"Natural gas processing consists of separating all of the various hydrocarbons and fluids from the pure natural gas, to produce what is known as 'pipeline quality' dry natural gas." – naturalgas.org

Removal of Impurities

To meet pipeline standards, water vapor, hydrogen sulfide (H₂S), and carbon dioxide (CO₂) must be removed from raw gas. If water vapor remains, it can combine with methane to form hydrates - ice-like crystals capable of clogging pipelines and valves. Dehydration is typically achieved using glycol (triethylene glycol heated to 400°F) or solid-desiccant systems, such as activated alumina or silica gel, for high-pressure applications.

Sweetening the gas involves removing H₂S and CO₂, which, if present in high amounts, classify the gas as "sour" (more than 5.7 milligrams of H₂S per cubic meter). The amine process, used in 95% of U.S. gas sweetening operations, relies on amine solutions like MEA (monoethanolamine) or DEA (diethanolamine) to chemically bind with these contaminants. The captured sulfur is then processed using the Claus process, which recovers 97% of the sulfur and accounts for 15% of the U.S. sulfur supply. Once impurities are removed, the focus shifts to recovering natural gas liquids (NGLs).

NGL Recovery and Fractionation

Natural gas liquids (NGLs) like ethane, propane, and butane are extracted to prevent operational issues and to tap into their higher market value. One common method involves absorption with a "lean" oil, which can recover up to 90% of propane and nearly all heavier NGLs. Another approach, cryogenic expansion, uses turbo-expanders to cool the gas to approximately -120°F. At this temperature, ethane and heavier hydrocarbons condense, while methane remains in a gaseous state. This process achieves a recovery rate of 90% to 95% for ethane.

After extraction, the mixed NGL stream undergoes fractionation to separate its components by boiling points. The process typically starts with a deethanizer to remove ethane, followed by a depropanizer for propane, a debutanizer for butanes, and finally a deisobutanizer to isolate iso-butane from normal butane. These separated products are then used in various applications, such as plastics manufacturing, heating fuels, and gasoline blending, leaving behind pipeline-quality methane ready for transport.

Transportation Through Pipeline Networks

Once processed, natural gas embarks on a journey through a vast pipeline network, ensuring it reaches power plants and other consumers. This process involves two key stages: gathering systems, which collect gas from production sites, and transmission pipelines, which carry it over long distances. Let’s break down how the gas is boosted and distributed before arriving at its final destination.

Gathering and Transmission Pipelines

The process begins with gathering pipelines, which are small-diameter lines - typically less than 6 inches wide - that connect wellheads to processing facilities and larger pipeline networks. These pipelines play a crucial role in moving raw gas from production areas to the next stage of its journey.

From there, transmission pipelines take over. These are the main arteries of the natural gas transportation system, with diameters ranging between 16 and 48 inches. Operating at high pressures - anywhere from 200 to 1,500 pounds per square inch (psi) - these pipelines efficiently transport gas over long distances. The U.S. boasts an impressive 305,000 miles of transmission pipelines, which move gas either across state lines (interstate) or within a single state (intrastate). By compressing the gas, reducing its volume by up to 600 times, these pipelines make long-distance transport economically feasible.

However, as gas flows through the pipelines, friction causes pressure to drop. To counter this, compressor stations are strategically placed every 40 to 100 miles along the pipeline. These stations, powered by turbines or electric motors, restore pressure and keep the gas moving at a steady rate. The entire network is monitored in real-time through SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems, which track critical metrics like flow rates, pressure, and temperature. This ensures that engineers can quickly address any issues that arise. After traveling long distances, the gas is distributed through specialized systems to reach its final users.

Local Distribution to End Users

For power plants, the journey is often more direct. These facilities typically connect to transmission pipelines via smaller branch lines, ranging from 6 to 16 inches in diameter, bypassing local distribution networks altogether. This direct connection eliminates the need for local distribution companies (LDCs), cutting costs and streamlining delivery. Interestingly, power plants and other large-volume users consume over 60% of the natural gas supplied to end users, even though they make up just 1% of the customer base.

When natural gas does pass through an LDC network, it enters at a "citygate" or "gate station", which serves as the transfer point between transmission and distribution systems. At this stage, the pressure is significantly reduced - from as high as 1,500 psi in transmission lines to as low as 3 psi in distribution networks, and eventually to just 1/4 psi by the time it reaches customer meters. Gate stations also play a critical role in metering the gas and adding mercaptan, a chemical that gives gas its distinctive odor for leak detection. However, power plants receiving gas directly from transmission lines often handle these functions independently at their own facilities.

Storage of Natural Gas for Demand Management

Once natural gas reaches the transmission system, it often moves into underground storage to help balance supply and demand. These storage facilities act as a buffer, allowing the industry to store gas when consumption is low and withdraw it during peak demand or supply interruptions. This ensures power plants have a steady and reliable fuel supply when needed.

This strategy works alongside the pipeline network, smoothing out demand fluctuations before the gas is conditioned and delivered to power plants.

Underground Reservoirs and Salt Caverns

In the U.S., three main types of underground storage are used, each with unique features. Depleted oil and gas reservoirs are the most common, making up 87% of total storage capacity. By early 2008, 327 out of 399 active storage sites were depleted reservoirs. These reservoirs are cost-effective to convert, with development costs around $5–$6 million per billion cubic feet (Bcf).

Salt caverns, while more expensive to develop - ranging from $10 million to $25 million per Bcf - offer a key advantage: high deliverability. They require only 20% to 30% cushion gas compared to the 50% to 80% needed by other types of storage. Salt caverns can handle full injection and withdrawal cycles in just 20 to 40 days, with withdrawal periods as short as 10 to 20 days. This makes them perfect for meeting the sudden spikes in demand typical of gas-fired power plants. In areas where depleted reservoirs aren't available, aquifer reservoirs are used, especially in the Midwest. However, these require more cushion gas and are less flexible operationally.

Storage facilities operate under pressure and categorize gas into two types: cushion gas, which stays in the reservoir to maintain pressure and flow, and working gas, which can be withdrawn as needed. The withdrawal rate is highest when the reservoir is full and gradually decreases as working gas is depleted and pressure drops.

Peak Demand and Supply Disruptions

Storage plays a critical role during peak demand periods and supply disruptions. Traditionally, gas was injected into storage during the off-peak months (April through October) and withdrawn in the winter heating season (November through March). However, the growing use of gas-fired electricity generation has introduced a secondary summer peak for cooling, fundamentally altering storage management.

Power plants, which account for over 60% of natural gas consumption among end users, heavily depend on high-deliverability storage to meet their rapid ramping needs. Regulations require pipelines to provide open-access storage, allowing power plants to lease storage capacity directly. This ensures generators can maintain fuel reliability and quickly respond to shifts in electricity demand.

The gap between rising demand and limited storage expansion has raised concerns. Between 1988 and 2005, U.S. natural gas demand grew by 24%, while storage capacity increased by only 1.4%. Former FERC Chairman Joseph T. Kelliher highlighted the issue:

"Since 1988, natural gas demand in the United States has risen 24 percent. Over the same period, gas storage capacity has increased only 1.4 percent. While construction of storage capacity has lagged behind the demand for natural gas, we have seen record levels of price volatility."

This mismatch has driven the need for more high-deliverability salt caverns to support the rapid ramping needs of power plants. With storage ensuring a steady supply, the next step involves preparing the gas for power plant operations.

sbb-itb-501186b

Delivery and Conditioning for Power Plants

Once natural gas is stored, it undergoes a conditioning process to meet the specifications required by turbines. This involves adjusting pressure, filtering impurities, and managing temperature to ensure the gas is safe and efficient for combustion. These steps are critical to delivering the gas to turbines in optimal condition.

Pressure Reduction and Cooling

Natural gas typically arrives at pressures between 800 and 1,200 psi. At gate stations, regulators reduce this pressure, meter the flow, and add odorants for safety purposes. The gas then passes through scrubbers and filters, which remove liquids like water or natural gas liquids, as well as solids that could harm turbine components. This filtration is crucial for protecting turbine blades and other equipment.

Temperature control is another key factor during compression. Compressing natural gas raises its temperature by about 7 to 8°F for every 100 psi increase. To address this, after-coolers are used to dissipate the heat before the gas continues through the fuel supply system. As Penn State Extension explains:

"As natural gas is compressed, heat is generated and must be dissipated to cool the gas stream before leaving the compressor facility".

Fuel Supply Systems for Gas Turbines

Power plants depend on integrated fuel gas systems to ensure the gas meets the precise requirements for combustion. These systems include station yard piping, gas metering equipment, and monitoring controls. Emergency Shutdown Systems (ESD) play a vital role in safety, isolating and venting gas if abnormal pressure drops or leaks are detected.

Most compressor stations adopt a "self-fueled" approach, using a small portion of the natural gas they handle to power their own engines or turbines. Additionally, backup generators ensure that critical systems - such as monitoring equipment, safety controls, and automated valves - remain functional during power outages.

Integration with Power Plant Operations

Once natural gas is conditioned for peak performance, power plants incorporate it into cutting-edge generation systems. Conditioned natural gas powers Combined Cycle Gas Turbine (CCGT) plants, which use a two-step process to extract maximum energy. The first step involves burning natural gas to operate a gas turbine, following the Brayton cycle. The turbine's exhaust, which reaches temperatures around 1,112°F (600°C), is then captured by a Heat Recovery Steam Generator (HRSG). This device uses the heat to convert water into steam, which powers a second turbine based on the Rankine cycle. This dual-turbine setup generates additional electricity without requiring more fuel. This approach not only boosts efficiency but also minimizes environmental impact.

Efficiency and Environmental Benefits

The efficiency of CCGT plants far surpasses that of simple-cycle gas turbines. While simple-cycle turbines typically achieve efficiencies between 20% and 35%, CCGT plants reach efficiencies of 50% to 60%, with some top-tier units exceeding 64%. A standout example is the EDF plant in Bouchain, France, which earned a Guinness World Record in April 2016 for achieving 62.22% efficiency. This plant used a General Electric 9HA turbine operating at temperatures between 2,600°F and 2,900°F, producing a combined output of 592 MW to 701 MW.

From an environmental standpoint, CCGT plants offer substantial advantages. Compared to traditional coal-fired power plants, they cut CO₂ emissions by about 65% and release significantly lower levels of nitrogen oxides (NOₓ) and sulfur oxides (SOₓ). Additionally, modern CCGT systems are highly efficient, consuming 80% of the natural gas used in power generation while producing 85% of the electricity generated from natural gas.

Grid Reliability and Quick Ramping

Modern CCGT plants also play a crucial role in stabilizing the power grid. They provide reliable, dispatchable capacity, which is essential as renewable energy sources like wind and solar become more widespread. Since renewable energy output can fluctuate with weather conditions, natural gas plants can quickly adjust their output to fill the gaps. Simple-cycle turbines and reciprocating engines are particularly effective, reaching full power within minutes to address sudden spikes in demand.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration highlights that newer CCGT plants are designed for "cycling behavior", allowing them to ramp up and down more quickly and respond to real-time grid needs better than older baseload models. As Laura Fletcher, Associate Product Manager at Yes Energy, puts it:

"CCGT plants are no longer solely baseload generators – they're strategic grid assets that provide firm, dispatchable capacity in an increasingly dynamic market".

Additionally, the latest CCGT plants commissioned between 2014 and 2023 demonstrated their effectiveness, with an average capacity factor of 66% in 2022, compared to simple-cycle plants, which averaged just 13% during peak demand periods.

Conclusion

The natural gas supply chain is a complex system that seamlessly integrates extraction, processing, transmission, storage, and delivery through an expansive network of 3 million miles of pipelines. This carefully coordinated process ensures power plants receive clean, pressurized natural gas exactly when they need it, laying the groundwork for the operational reliability discussed in later stages.

Managing the supply chain effectively plays a crucial role in supporting grid reliability. Processing plants remove impurities to produce pipeline-quality gas, which helps avoid equipment damage and operational disruptions. Meanwhile, underground storage facilities - holding over 80% of their capacity in depleted reservoirs - serve as essential buffers against sudden demand spikes and supply interruptions.

Firm contracts also play a pivotal role. In 2016, 71% of power plant natural gas was secured through these agreements, ensuring priority access during peak demand periods. This became even more critical after 2015, when the electric power sector overtook other sectors as the largest consumer of natural gas in the U.S.. The U.S. Energy Information Administration highlights this growing dependency:

"As the share of natural gas used for power generation has increased, so has the interdependence between natural gas supply and infrastructure and electric power generator operations".

In 2023, pipeline companies delivered 75% (27.1 Bcf/d) of the natural gas used for electricity generation. This supply supports both steady baseload generation and the quick ramping capabilities needed to balance the variability of renewable energy sources. As previously noted, strategic storage and pressure management are essential for aligning supply with demand. Together with firm contracts, these measures ensure a reliable and continuous fuel supply to meet electricity needs.

FAQs

How does the natural gas supply chain affect power plant efficiency?

The natural gas supply chain is essential for keeping power plants running smoothly, as it ensures a steady and reliable fuel source. This chain involves several key steps: extracting natural gas, processing it to remove impurities, and transporting it through pipelines to maintain consistent delivery.

A well-functioning supply chain helps avoid fuel shortages or quality problems that could disrupt power generation. By guaranteeing a continuous flow of clean natural gas, power plants can perform at their best, providing dependable electricity for consumers.

Why are underground storage facilities important for managing natural gas supply and demand?

Underground storage facilities play a key role in ensuring a steady natural gas supply by managing seasonal shifts in demand. During the summer, when demand typically dips, natural gas is stored in these facilities. Then, as winter arrives and consumption spikes, the stored gas is withdrawn to meet the increased need.

This approach helps maintain a consistent supply for power plants and other consumers, reducing the risk of shortages and keeping prices more stable year-round.

How do combined cycle gas turbine plants improve grid reliability compared to traditional power plants?

Combined cycle gas turbine plants enhance grid reliability by combining gas and steam turbines to generate electricity. This setup boosts efficiency, producing about 50% more electricity from the same amount of natural gas compared to traditional methods.

Another advantage is their adaptability. These plants can quickly adjust power output to match fluctuating grid demands, making them a dependable solution for today's energy requirements.