Community Energy Systems vs. Centralized Grids

Share

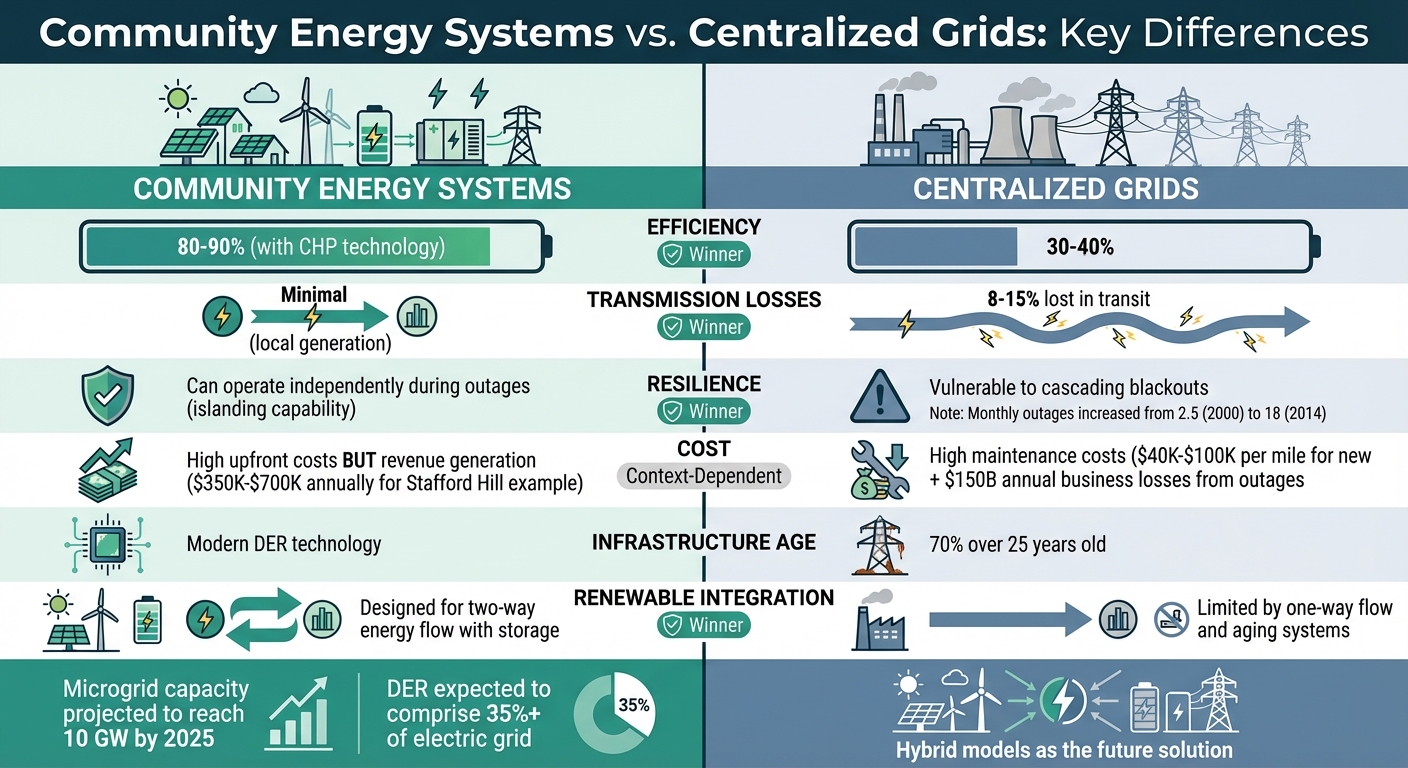

Community energy systems and centralized grids represent two distinct approaches to power generation and distribution. Here's the key difference: centralized grids rely on large, far-off power plants and extensive transmission networks, while community systems focus on localized energy production using resources like solar panels, wind turbines, and batteries.

Key Points:

- Efficiency: Community systems achieve up to 90% efficiency with local generation and technologies like Combined Heat and Power (CHP), compared to 30%-40% for centralized grids.

- Resilience: Microgrids in community systems can operate independently during outages ("islanding"), unlike centralized grids prone to cascading failures.

- Energy Losses: Centralized grids lose 8%-15% of electricity during transmission, while community systems minimize these losses by generating power close to users.

- Cost: Centralized grids require expensive infrastructure upgrades, while community systems have high upfront costs but generate revenue through services like grid support.

- Renewables: Community systems integrate solar and wind more seamlessly, while centralized grids struggle with their one-way energy flow and aging infrastructure.

Quick Comparison:

| Factor | Community Energy Systems | Centralized Grids |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | Up to 90% with CHP | 30%-40% |

| Transmission Losses | Minimal (local generation) | 8%-15% |

| Resilience | Can operate independently during outages | Vulnerable to widespread blackouts |

| Cost | High upfront; potential revenue streams | High maintenance and upgrade costs |

| Renewable Integration | Designed for two-way energy flow | Limited by aging, one-way systems |

Community systems are gaining traction across the U.S., with microgrids projected to reach 10 GW of installed capacity by 2025. While centralized grids remain essential for urban areas, hybrid models combining both approaches show promise for a more efficient and resilient energy future.

Community Energy Systems vs Centralized Grids: Efficiency, Cost, and Resilience Comparison

Microgrids vs. Traditional Grids

Design Principles: Community Energy Systems vs. Centralized Grids

The main distinction between these two systems lies in their scale and energy flow. Centralized grids operate on a top-down model, relying on massive gigawatt-scale generating units and an extensive network of high-voltage transmission lines that stretch for hundreds of thousands of miles. In contrast, community energy systems adopt a ground-up approach. These systems range from small "nanogrids", which can power individual buildings with less than 100 kW, to larger community clusters that operate in the multi-megawatt range. This difference shapes how each system handles scalability and local energy needs.

Scalability vs. Localization

Centralized grids demand major investments to accommodate even small increases in energy demand. Expanding capacity often involves constructing new transmission lines and upgrading substations - projects that can take years and cost millions of dollars. On the other hand, community energy systems are far more flexible. They allow for "plug-and-play" scalability, enabling communities to add new distributed energy resources locally as their energy needs grow. This localized approach eliminates the need for costly transmission infrastructure.

Take the University of Texas at Austin as an example. The university operates a 137 MW microgrid powered by a combined heat and power generator. This system captures 88% of the energy from fuel, far surpassing the 30%–40% efficiency typical of traditional coal plants. By distributing steam and chilled water through underground pipes, the microgrid is 30 times more reliable than the national grid and saves the university over $4 million annually.

While scalability is a critical advantage, the ability to seamlessly integrate renewable energy sets these systems even further apart.

Flexibility and Renewable Integration

Centralized grids face significant challenges when it comes to the two-way power flow required by modern renewable energy systems. They were originally designed for one-way energy distribution - from large-scale facilities to end users. In contrast, community energy systems are inherently more adaptable. They’re built to handle diverse technologies and stabilize variable renewables like solar and wind through local storage solutions.

A great example is the Stafford Hill microgrid in Vermont, developed by Green Mountain Power. This was the first U.S. microgrid to rely solely on solar and storage. It combines 2.5 MW of solar capacity with 4 MW of battery storage, providing full backup power to a local high school while generating $350,000 to $700,000 annually by offering frequency regulation services to the larger grid.

Another hurdle for centralized grids is their aging infrastructure. Roughly 70% of transmission lines and transformers are more than 25 years old, making it difficult for these systems to adapt to renewable energy demands. Community energy systems, built with modern technology, can easily integrate resources like solar panels, small wind turbines, and fuel cells without the need for extensive retrofitting or upgrades.

Advantages and Disadvantages: A Direct Comparison

Efficiency and Energy Losses

Centralized grids stretch across an extensive 5.7 million miles, which leads to a notable downside: energy loss. Between 8% and 15% of electricity vanishes as heat before it even reaches homes or businesses. As Elisa Wood, Editor-in-Chief of Microgrid Knowledge, puts it:

Delivering power from afar is inefficient because some of the electricity – as much as 8% to 15% – dissipates in transit. A microgrid overcomes this inefficiency by generating power close to those it serves.

Community energy systems, on the other hand, produce electricity locally, cutting out most of these transmission losses. Plus, many of these systems use Combined Heat and Power (CHP) technology, which captures waste heat and repurposes it for heating and cooling. This approach boosts total efficiency to 80% to 90%, far surpassing the 30% to 40% efficiency of centralized plants. All-DC microgrids take it a step further by eliminating AC-to-DC conversion losses, which can range from 5% to 15%. These efficiency differences highlight the operational and economic advantages of community systems, which we’ll dive into next.

Cost Implications

The financial side of the debate is anything but simple. Centralized grids demand constant investment to maintain and upgrade their aging infrastructure. For example, new distribution lines cost anywhere from $40,000 to $100,000 per mile, depending on the terrain and labor involved. On top of that, electricity blackouts hit U.S. businesses hard, racking up an estimated $150 billion in annual losses.

Community energy systems do come with a hefty upfront cost for specialized equipment, controllers, and storage. However, they can create revenue streams that centralized grids simply can’t. Take the Stafford Hill microgrid in Vermont, for instance - it generates between $350,000 and $700,000 annually through services like frequency regulation and grid support, with a payback period of less than 10 years. Another example is Kodiak Island, Alaska, where a community microgrid has achieved nearly 100% renewable energy reliance, saving around $4 million per year compared to diesel-only power generation. With the steady decline in costs for distributed generation and energy storage, the financial case for community systems keeps getting stronger.

Resilience and Outage Recovery

When it comes to handling storms and disasters, community energy systems shine. They can "island" themselves, meaning they disconnect from the main grid and operate independently during emergencies. A prime example is Princeton University's microgrid. During Hurricane Sandy in October 2012, it continued to function for three days, powered by a 15 MW CHP generator and 5.3 MW of solar, while the surrounding centralized grid went down.

In contrast, centralized grids are more prone to widespread failures. Something as small as a tree falling on a transmission line can cascade into blackouts across multiple states. Monthly power outages in the U.S. skyrocketed from just 2.5 in 2000 to nearly 18 by 2014. Between 2003 and 2012, weather-related grid disruptions caused annual losses of $18 billion to $33 billion. And let’s not forget the 2003 Northeast Blackout, which affected 50 million people and 61,800 MW of load.

Comparison Table

Here’s a quick breakdown of the key factors:

| Factor | Community Energy Systems | Centralized Grids | Winner/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | 80%–90% with CHP | 30%–40% average | Community systems |

| Transmission Losses | Minimal (local generation) | 8%–15% loss in transit | Community systems |

| Cost | High upfront; revenue from grid services | High maintenance for aging lines | Depends on scale and timeframe |

| Resilience | Can island; localized failures | Vulnerable to cascading blackouts | Community systems |

| Renewable Integration | High adaptability with storage | Slower transition; one-way flow | Community systems |

| Infrastructure Age | Modern DER and controllers | 70% over 25 years old | Community systems |

sbb-itb-501186b

Applications in the United States

Case Study: Community Solar Microgrids

Across rural and suburban parts of the U.S., small-scale solar microgrids are proving their value, especially in areas where aging infrastructure struggles to keep up. Take Borrego Springs, California, for example. Back in 2013, the community implemented a microgrid combining diesel generators, rooftop solar panels (597 kW total), and a 26 MW solar array. This setup allowed the town to "island" itself - essentially operate independently - during severe storms, ensuring critical cooling during extreme heat. By 2015, it became the first U.S. microgrid to rely heavily on solar power and storage during a planned outage.

Another example comes from the San Pasqual Band of Mission Indians in California. They added 290 kW of solar PV and battery storage to cut their reliance on the main grid and enhance energy independence. In Vermont, the Stafford Hill microgrid broke new ground as the first in the U.S. to rely solely on solar (2.5 MW) and battery storage (4 MW) for backup power. This system can provide indefinite power to a local high school, which doubles as an emergency shelter. These cases highlight the dual advantages of energy independence and stronger resilience.

While rural communities benefit from the adaptability of microgrids, urban areas remain tied to centralized systems due to the sheer scale of their energy needs.

Urban Dependence on Centralized Grids

Cities face a different set of challenges compared to rural areas when it comes to energy. Urban centers require gigawatt-scale power plants and sprawling transmission networks to power millions of homes, businesses, and industries. However, the vulnerabilities of these centralized systems are becoming increasingly clear. During Hurricane Beryl in July 2024, for instance, a grid failure left 2.26 million customers in the Houston area without power. The outage was worsened by fallen poles and wires, which can take weeks to repair. Michael Webber, an energy expert and professor at the University of Texas at Austin, summed it up:

The weak point is the wires and poles, and basically always has been. But it's not a priority for the state.

In response to these weaknesses, urban planners are exploring microgrids for critical facilities like hospitals, data centers, and universities - places where reliable power is absolutely essential.

Hybrid Models for Sustainability

To balance the need for localized resilience with the demands of large-scale urban energy, hybrid models are emerging as a solution. These systems combine community microgrids with centralized grids, allowing for optimized performance during times of stress. Community microgrids in these models can remain connected to the main grid but have the ability to "island" in emergencies, ensuring local power stays on. They can also support the larger grid by regulating voltage and frequency or even restarting the system after a blackout through a process known as a "black start".

One standout example is the Texas Aggregate Distributed Energy Resource (ADER) Pilot, launched in early 2023. This program enrolls customers in Houston and Dallas - many using Tesla Powerwall batteries - and compensates them for feeding energy back into the grid during peak demand. By late 2024, this initiative had effectively created a 15–20 MW virtual power plant. Another example is the Bronzeville Community Microgrid in Chicago, developed by Commonwealth Edison (ComEd). This neighborhood-scale system incorporates rooftop solar, community solar, batteries, and EV chargers. It not only helps cushion against power shortages but can also operate independently during outages. Amy Heart, Senior VP of Public Policy at Sunrun, explained:

By reducing barriers and making it more financially affordable to invest in these on-site generation and storage assets, you're going to be able to create not only a more resilient grid but a more affordable grid.

Equipment Sourcing for Community Energy Systems

Required Equipment for Community Systems

Creating a community energy system requires careful selection of specialized equipment tailored for localized energy generation. Unlike traditional centralized grids, these systems rely on distributed energy resources, such as rooftop solar panels, small-scale wind turbines, and emergency standby diesel generators. Battery storage systems - whether wall-mounted units or server rack setups - are equally important, as they store surplus energy for times when generation dips.

Key components for power conversion and safety include hybrid/grid-tie inverters that convert DC to AC, microinverters that enhance individual panel output, and charge controllers. Safety elements like breakers, switches, fuses, and combiner boxes are critical for ensuring the system operates securely. Unlike centralized grids that depend on high-voltage transmission lines, these components connect to a lower-voltage distribution grid, making them more community-focused.

Distribution and control equipment act as the backbone of the system. Three-phase substation transformers and distribution transformers regulate voltage levels, while transfer switches ensure safe and reliable operation, especially during emergencies. Control software and communication tools enable "islanding", a feature that allows the system to disconnect from the main grid and function independently during outages. As the U.S. Department of Energy points out:

While the grid was designed to generate power at large facilities and move it through the transmission grid to the distribution grid for consumption, DER enable local generation and consumption of electricity.

Choosing the right components is crucial, and having a streamlined sourcing process can simplify the journey for communities.

Why Choose Electrical Trader?

Navigating the challenges of sourcing equipment for community energy systems can be daunting, especially with high upfront costs. That’s where Electrical Trader steps in as a one-stop platform for essential components. By offering both new and used electrical equipment, Electrical Trader helps communities access what they need without exceeding their budgets. Their inventory includes everything from 3-phase substation transformers for voltage regulation to emergency standby diesel generators for black start capabilities and grid-forming power. They also provide a comprehensive range of breakers, switchgear, and power distribution equipment.

Whether you’re setting up a microgrid for a single building or a substation supporting hundreds of users, Electrical Trader is tailored to meet the specific demands of community energy projects. With more than 12 million distributed generation units already in operation across the U.S., having access to reliable equipment through a centralized platform simplifies the sourcing process. Electrical Trader’s extensive inventory - from compact inverters to large-scale substation transformers - empowers communities to build robust, locally managed energy systems.

Conclusion: Community Energy Systems vs. Centralized Grids

Key Takeaways

Centralized grids excel in large-scale energy distribution and cost efficiencies but face challenges like aging infrastructure and vulnerability to extreme weather. The American Society of Civil Engineers gave the U.S. electric grid a concerning "D+" grade, and power outages cost U.S. businesses an estimated $150 billion annually.

On the other hand, community energy systems leverage localized CHP (Combined Heat and Power) technology to deliver higher efficiency while cutting energy waste and operational costs. A standout example is a 137 MW CHP microgrid that has achieved multi-million-dollar savings each year.

Hybrid models that combine community systems with centralized grids offer a promising middle ground. These setups provide critical backup during outages and enhance grid stability through islanding. For instance, during Hurricane Sandy in October 2012, Princeton University's microgrid kept the campus powered for three days while the surrounding centralized grid was down. As the Institute for Local Self-Reliance aptly puts it:

Microgrids are just one more way that the grid is becoming democratized and miniaturized. To some extent they are unstoppable, the continuation of economic and technology trends favoring local, decentralized power generation.

This comparison highlights the growing momentum for change in the U.S. energy landscape.

Future of Energy Systems

The shift toward decentralization, decarbonization, and democratization is reshaping energy systems. Rather than replacing centralized grids, community energy systems are evolving to complement them by offering services like frequency regulation, voltage control, and demand response. By 2025, microgrid capacity is expected to hit 10 GW, with distributed energy resources projected to make up over 35% of the electric grid.

Policy changes are speeding up this transition. States like New York, California, and Connecticut are investing in microgrid initiatives, such as New York's $40 million "New York Prize", to integrate community energy systems. These hybrid configurations not only allow communities to maintain power during outages through islanding but also support grid stability during peak demand. This evolution strengthens community resilience and lays the groundwork for a modern, sustainable energy system in the U.S.

FAQs

How do community energy systems manage power outages compared to centralized grids?

Community energy systems, commonly structured as microgrids, are designed to keep power flowing locally, even during large-scale outages. By integrating distributed energy resources such as solar panels, battery storage, and backup generators, microgrids can disconnect from the main grid and function independently. This ability, called "islanding", ensures that essential services like hospitals and water systems remain operational by balancing local energy production and consumption without external support.

Unlike microgrids, centralized grids rely on massive power plants and extensive networks of transmission lines. A single fault in these systems can trigger outages that spread across entire regions, leaving thousands in the dark until repairs are completed. Microgrids, on the other hand, focus on powering critical infrastructure and can sustain operations for days. For instance, in several cases, towns equipped with solar and battery systems continued running smoothly during prolonged outages.

Building or upgrading such robust systems often requires specialized equipment, including breakers, transformers, and voltage management tools. Electrical Trader offers a wide range of new and used electrical components to help communities develop dependable microgrids and stay prepared for unexpected power failures.

What financial advantages do community energy systems offer despite their initial costs?

Community energy systems can turn hefty upfront expenses into substantial long-term savings for both homeowners and local neighborhoods. Take rooftop solar or shared solar programs as examples - homeowners can save anywhere from $12,000 to $14,000 over the system's lifetime compared to sticking with traditional utility companies. Plus, these systems can boost property values by about $4,000 per kilowatt installed. Beyond personal savings, locally owned energy systems bring additional perks, like creating new jobs and keeping economic gains within the community.

Another advantage is the reduced dependence on centralized power grids, which helps shield consumers from unpredictable electricity price spikes. Operators can tap into stored energy or generate their own during high-demand periods, keeping costs in check. These systems also cut down the need for costly grid upgrades, which can result in lower utility rates for everyone. While the upfront costs might seem steep, the local economic benefits and significant long-term savings often make community energy systems a wise investment.

Why are community energy systems better at using renewable energy compared to centralized grids?

Community energy systems, such as microgrids, focus on generating electricity right where it's used. They often rely on renewable sources like rooftop solar panels, wind turbines, or small-scale hydroelectric setups. By producing energy locally, these systems cut down on the losses that occur during long-distance transmission, making them more efficient than the traditional centralized grid.

What makes these systems even more effective is their ability to align with local energy demands. By pairing renewable energy installations with tools like on-site storage and smart controls, microgrids can balance supply and demand in real time. They can even operate independently from the main grid during outages, ensuring uninterrupted power. This adaptability also means they can handle more renewable energy without straining the grid.

Building and maintaining these systems requires specialized equipment, such as inverters, transformers, and energy storage devices. Platforms like Electrical Trader play a key role by offering a wide selection of these essential components, making it easier to develop renewable-focused community energy projects.